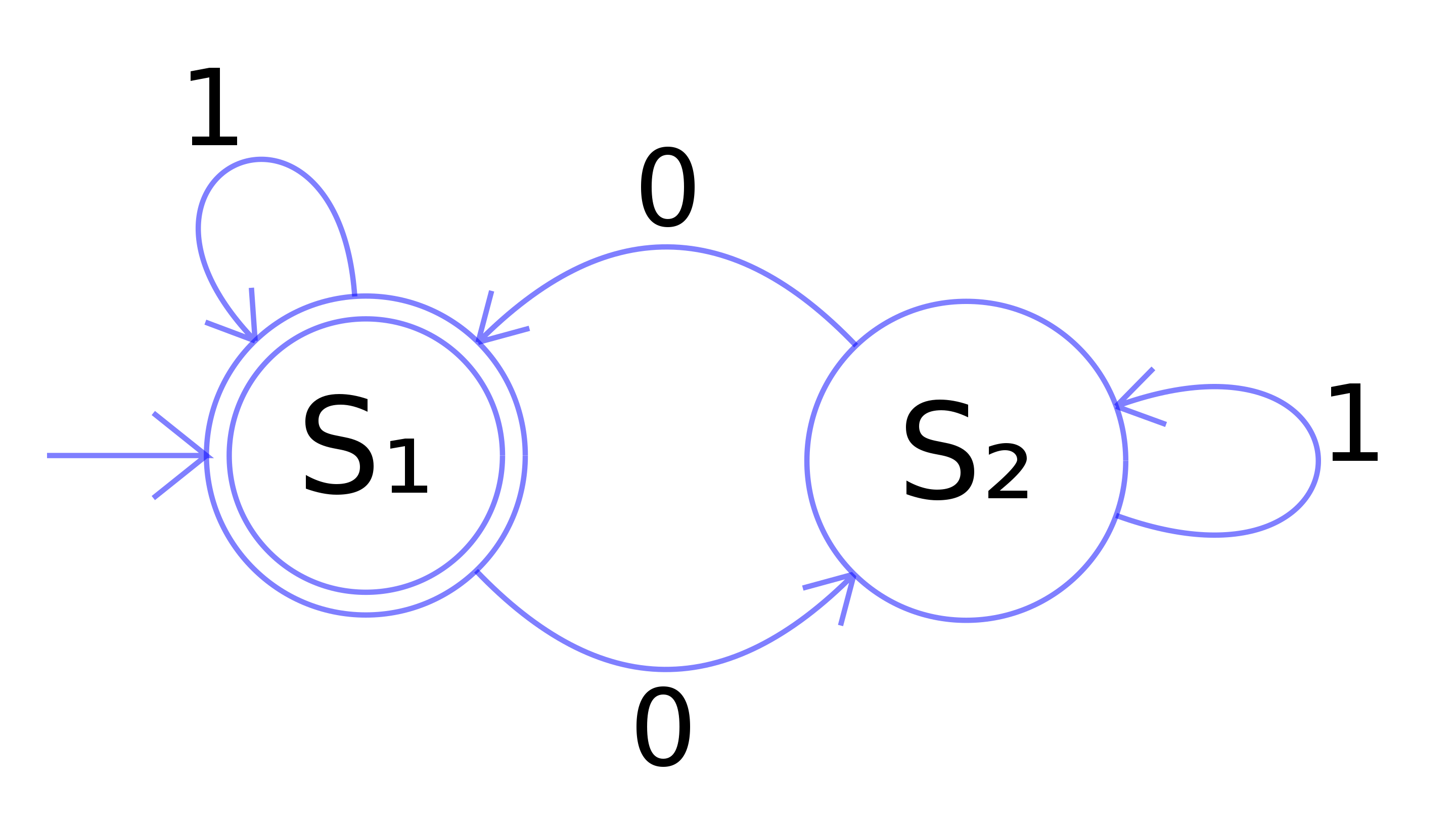

The mathematical notion of automaton indicates a discrete-time system with finite set of possible states, a finite number of inputs, a finite number of outputs, and a transition rule which gives the state at the next step in terms of the state and inputs at the previous step.

A Cellular Automaton applies this notion in parallel to a cellular space, in which each cell of the space is a stateful automaton.

Christopher Adami describes CAs as the first "artificial chemistries", since they operate as a medium to research the continuum between the inanimate (such as molecules in crystal and metalline structures) and the living (such as cells of a multi-cellular organism). Thus they can be used to model all kinds of information processing and development in biological systems, as well as questions of life's origins. (However the computational cellular systems we will visit are far, far simpler than biological cells.)

The CA model was propsed by Stanislaw Ulam and used by von Neumann -- in the 1940's -- to demonstrate machines that can reproduce themselves. Decades later Christopher Langton proposed a more concise self-reproducing CA, which has since been further improved upon using artificial evolutionary techniques:

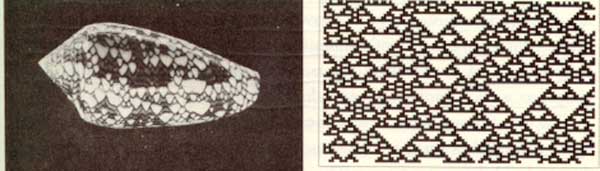

Stephen Wolfram, author of Mathematica, performed extensive research on CAs and uncovered general classes of behaviour comparable to dynamical systems. A commonly referenced example is his 'rule 30', which is a 1D CA displayed below as a stacked trace (history goes down) -- whose pattern is reminiscent of some naturally occurring shell patterns:

Here are some of the well-known 1D rules:

See the Pen 1D Rules: 2019 by Graham (@grrrwaaa) on CodePen.

Wolfram divided CA into four classes, according to their long-term behavior:

Over here a 3D cellular automaton is taking over Minecraft, and here is a self-replicating computer in 3D.

The essential components that define a cellular system are:

Cellular space: A collection of cells arranged into a discrete lattice, such as a 1D strip, a 2D grid, or a 3D volume.

Cell states: The information representing the current condition of a cell. In binary CAs this is simply either 0 or 1.

Initial conditions: What state the cells are in at the start of the simulation.

Neighborhood: The set of adjacent/nearby cells that can directly influence the next state of a cell. The most common 2D neighborhoods are:

State transition function: The rule that a cell follows to update its state, which depends on the current state and the state of the neighborhood. It gives the cell state[t+1] as a function of the states[t] of itself and neighbours.

Time axis: The cells are generally updated in a discrete fashion, which may be synchronous (all cells update simultaneously) or asynchronous (cells update sequentially).

Boundary conditions: What happens to cells at the edges of the space. A periodic boundary 'wraps around' to the opposite edge; a static boundary always has the same state, a reflective boundary mirrors the neighbor state.

The most famous CA is probably the Game of Life. It is a 2D, class 4 automata, which uses the Moore neighbourhood (8 neighbours), and synchronous update. The transition rule can be stated as follows:

If the neigbor total is exactly 3: New state is 1 ("reproduction")

Else: State remains the same ("dead")

It is thus an example of a outer totalistic CA: The spatial directions of cells do not matter, only the total value of all neighbors is used, along with the current value of the cell itself. Note also that these rules mean that the Game of Life is not reversible: from a given state it is not possible to determine the previous state.

The Game of Life produces easily recognizable higher-level formations including stable objects, oscillatory objects, mobile objects and objects that produce or consume others, for example, which have been called 'ponds', 'gliders', 'eaters', 'glider guns' and so on.

This CA is so popular that people have written Turing machines and, recursively, the Game of Life in it.

If the cells are densely packed into a regular lattice structure, such as a 2D grid, they can efficiently be represented as array memory blocks. The state of a cell can be represented by a number.

This is similar to the representation of an image as data -- a grid of pixel values, which are just numbers in a lattice.

The rules themselves can be translated pretty efficiently to procedural code, using if/else conditions.

One complication is that the states of the whole lattice must update synchronously. A naive implementation will thus update cells one at a time, and the neighborhood of a particular cell will contain both 'past' and 'future' states. One way to work around this is to maintain two copies of the lattice; one for the 'past' states, and one for the 'future' states. The transition rule always reads from the 'past' lattice, and always writes to the 'future' lattice. After all cells are updated, either the 'future' is copied to the 'past', or the 'future' and 'past' lattices are swapped, since the future of yesterday is the past of tomorrow.

This technique is called double-buffering, and is widely used in software systems where a parallel process interacts with a serial machine. It is used to render graphics to the screen, for example.

In past years we have implemented our CAs using operations on buffers in the CPU, like this:

See the Pen 2019 DATT4950 Jan 3 by Graham (@grrrwaaa) on CodePen.

However the nature of CAs makes them incredibly suitable for implementation using GPUs:

It turns out that by using GPU shaders, our cellular automata can run tends or even hundreds of times faster than on the CPU. Or put another way, we can make them at much higher resolutions, or make them much more complex, and still get good update frame rates.

So this year, we're going to implement our CAs using fragment shaders in GLSL. GLSL is a way to write programs that will run directly on your GPU. GLSL can be used in the web like on ShaderToy, or in Three.js, or basically any web page in a modern browser -- even when opened on your phone or a VR headset like the Quest 3. GLSL is also used in desktop OpenGL envionments, including TouchDesigner, Max/MSP/Jitter, Ossia, Hydra, and so on. It can also be used in Unity or Unreal, though they prefer you to use a more abstract language (HLSL) which then translates to GLSL. It is an incredibly useful skill for media arts today.

A really convenient way to explore this is using Shadertoy.com, a browser-based editor and viewer for fragment shaders. It's free to create an account so that you can save your shaders, and so long as you save them as "public", you can share them via the URL. Also, it's relatively easy to move shaders written in ShaderToy to other environments, such as Max/Jitter, TouchDesigner, Three.js, OpenFrameworks, Cinder, etc., and with a little more work, Unity, Unreal, Godot, etc.

A quick tutorial on GLSL in Shadertoy

Planning

How to initialize the field -- random on/off cells?

The next frame is a function of the previous frame; so we need a Buffer for the feedback loop

We will need an initialization event (frame zero? keyboard input?)

We need to read neighbor pixels via coordinate operations

Boundary conditions: we can use the wrap settings of the iChannel input, or define our own

Texture values are floating points (0.0 to 1.0), but we need integer values (0 or 1), so we can count them. We can cast a comparison to integer (e.g. int(N.x > 0.))

Can we draw input with the mouse via iMouse?

Can we rewrite it using mat3 kernels?

We actually have 4 values per pixel (R, G, B, A), but we are only using 1 right now. Can we use the others to visualize something useful?

Questions

Can you try different thresholds of neighbors for death and rebirth? Do you get complex behaviour, or one of Wolfram's other classes? Can you figure out what the rules need to be complex?

Will it run forever?

A backround noise can be added, such that from time to time a randomly chosen cell changes state. Try adding background noise to the Game of Life to avoid it reaching a stable or cyclic attractor. But too high a probability and it descends into noise. Try adding a temperature control to control the statistical frequency of such changes. Could something intrinsic to the system determine temperature? Could this vary over space?

Starting from this basis, what do you think would be interesting to change?

More variations are possible by modulating the basic definition of a CA, some of which have been explored more than others.

Look at the basic definition of CAs we saw above, and think: what could be varied from how the Game of Life works, but still be within the definition of a CA? What do you think we could change to make it more interesting?

Your Assignment 1 will a novel Cellular Automata of your own design & invention, implemented using Shadertoy.

Game of Life has only two states, 0 and 1, but we could have more states. For example, here is "Brian's Brain". In this CA there are 3 states, which we typically encode as 1.0, 0.5, and 0.0.

https://www.shadertoy.com/view/t3tcDN

This example has three named states -- but one of them includes a whole set of possible values.

It is initially described as an infection model, but really it is something quite a bit stranger.

0.0 means healthy

1.0 means sick

Posisble values between 0.0 and 1.0 mean infected but not yet sick.

In the reference implementation, there are 254 possible values of increasing infection, so this is actually a 256-state automaton.

https://www.shadertoy.com/view/3XcyRs

This system typically goes through several stages:

The crucial parameter to vary these behaviors is the sickness rate.

The spiral patterns here are characteristic of Reaction Diffusion systems, which we will explore further later.

See http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/016727898990081X#

In this case the transition rule is not deterministic, but includes some (pseudo-)randomized factors. This can help avoid the CA falling into a stable or cyclic pattern -- at the risk of descending into uninteresting noise.

See the Pen Forest Fire: 2019 by Graham (@grrrwaaa) on CodePen.

Unfortunately, this one poses a few challenges in GLSL, because of the extremely low numbers we use in the probability tests. The reason is limits of floating point resolution on the GPU, and the quality of the random number generator. We can work around this partly by applying our probability tests against two values at the same time, e.g.

if (noise.x < growth_probability && noise.y < growth_probability) {}

https://www.shadertoy.com/view/tXdcDN

Play with different values to see what you find. There can be temporal and spiral oscillations hiding in here.

The rule is not the same for all cells. Spatial inhomogeneity can be interesting to simulate different geographies (such as boundaries). The simplest option is to prime the system with inhomogeneous initial conditions, but these differences can quickly dissipate, whereas varying other components of a CA spatially can have more profound results (though, as with randomness, care may need to be taken that these differences do not overly dominate the process).

Temporal non-homogeneity can be used to perform a sequence of different filters, or otherwise help to build long- as well as short-term arcs of behaviour.

One has to be careful though: it could be that introducing these variations is not really different to a slightly more complex, but homogenous, CA.

A mobile CA has a notion of active cells. The transition rule is only applied to active cells, and must also specify a related cell (such as one of the neighbors) of the current active cell as the next active cell. (This could also be partly probabilistic.)

There could be more than one 'active cell' -- there could even be a list of currently active cells. Non-active cells are then described as "quiescent". But what happens if two active cells occupy the same site?

See the Pen Langton's Ant: 2019 by Graham (@grrrwaaa) on CodePen.

A variation with multiple ants:

See the Pen Multiple Langton Ants: 2019 by Graham (@grrrwaaa) on CodePen.

The [original video by Christopher Langton](http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w6XQQhCgq5c), including examples of multiple ants (and music by the Vasulkas):How would you implement this in GLSL?

Every cell has the following values:

On every step, check the 4 neighbours; if there's an ant, and it is heading our way, move it into our cell, rotate its direction, and flip our cell value

https://www.shadertoy.com/view/W33yRS

Mitchel Resnick's termite model is a random walker in a space that can contain woodchips, in which each termite can carry one woodchip at a time. The program for a termite looks something like this:

If I am carrying a wood chip, drop mine where I am and turn around

Else move forward and pick up the woodchip

Over time, the termites begin to collect the woodchips into small piles, which gradually coalesce into a single large pile of chips.

This is a trickier model to implement in GLSL -- it takes careful attention to movement of cells to make sure the number of termites does not accidentally increase! But it's the same basic idea as Langton's Ant. Remember: the fragment shader program is always from the perspective of the cell (not the ant/termite): a cell needs to know if a termite is entering it from a neighbor, or if a termite currently in the cell will remain there. If neither of those cases are true, then the cell will end the frame with no termite present.

https://www.shadertoy.com/view/33cyRS

This concept of a cell's perspective on occupancy can be extended to modeling particles in a cellular fashion!

If the transition rule (or, the set of transition rules as a whole) is careful to preserve a total cell values before and after, it can give the impression of a mass-conserving system, such as modeling the motion of particles and fluids. The elementary 1D traffic CA (rule 184) is a simple particle CA.

Sometimes this is considered "mass preserving". That is, the total amount of "stuff" in the world never changes, it just moves around.

Note that our Ant and Termite models are not strictly mass-preserving: can you explain why?

Mass-preserving CAs can be guaranteed not to dissolve into homogenous final states of all-black/all-white/etc. -- which can alleviate any need for an external limiter to keep the balance -- but this does not mean they won't find a stable or cyclic end. (On the other hand, CAs whose rules do not appear to preserve mass can still avoid dissolution into homogeneity.)

Note that mass-preservation does not imply that the system is reversible. Reversibility is quite a different property, which states that each output neighbourhood can only be caused by a single predecessor neighbourhood. Some, but certainly not all, particle CAs are reversible.

In 1969, German computer pioneer (and painter) Konrad Zuse published his book Calculating Space, proposing that the physical laws of the universe are discrete by nature, and that the entire universe is the output of a deterministic computation on a single cellular automaton. This became the foundation of the field of study called digital physics. Zuse's first model is a 3D particle CA.

A CA-inspired digital physics hypothesis is currently being promoted by Stephen Wolfram, as described in his magnum opus A New Kind Of Science.

Those models are determinsitic, but particle CA can also use probabilistic rules to simulate brownian motions (like our termite explorers) and other non-deterministic media (but the rules would usually still need to be matter/energy preserving over long-term averages -- i.e. probabilities must balance to preserve mass). Particle CAs can also benefit from the inclusion of boundaries and other spatial non-homogeneities such as influx and outflow of particles at opposite edges to create more interesting gradients or otherwise keep the system away from equilibrium (a dissipative system).

We have already seen one example of a probabilistic CA above (the Forest Fire model).

The key factor in a probabilistic model is how you calculate the probability of a change. In the forest fire model, these were simply constants, but are only tested according the presence of particular types of neighbors (burning trees, empty land, etc.).

In many probabilistic models, the probability of a change depends on the local difference of a cell from its neighbors. This kind of model is sometimes called a contact process model. It can be used to model the spread of infection, voter bias, or behaviours of fundamental physics.

A simple infection model, for example: - infected sites become healthy at a constant rate - healty sites become infected at a rate proportional to the number infected neighbours

Could you implement this? Could you extend it to incorporate effects of vaccination, social distancing, multiple diseases, etc.?

The Ising model of ferromagnetism in statistical mechanics models the probability of a point in space flipping between positive or negative spin. The probability of this change happening depends on the local entropy: the probability is higher if the change of state would move the site closer to energetic equilibrium with its local neigborhood. That is, nearby cells are more likely to become the same than to become different.

However, there is also an increasing chance of a site changing state according to the local temperature. Thus at high temperatures, the system remains noisy, while at lower temperatures it gradually self-organizes into grouped zones with equal spin. This idea of a temperature control generalizes to many kinds of systems.

This creates two opposing forces, one diffusion like, which promotes order, and one destructive, which induces chaos.

https://www.shadertoy.com/view/tXtcz2

The cellular Potts model (also known as the Glazier-Graner model) generalizes probabilistic CA beyond the two states of the Ising model to allow morestates, and in some cases, an unbounded number of possible site states; however it still utilizes the notion of statistical movement toward neighbor equilibrium to drive change, though the definition of a local Hamiltonian. Variations have been used to model grain growth, foam, fluid flow, chemotaxis, biological cells, and even the developmental cycle of whole organisms.

Note that in this subfield of research, the term cell is used not to refer to a site on the lattice, but to a whole group of connected sites that share the same state. So in modeling foam, a cell represents a single bubble, and is made of one or more sites. Most changes therefore happen at the boundaries between these cells.

Stan Marée used this model to simulate the whole life cycle of Dictyostelium discoideum!

States need not be discrete integers -- in other systems the state could be represented by an n-tuple of values, or a recursive structure allowing unbounded complexity.

The CAs we have looked at so far are mostly discrete, and this is often evident in the results. There are several ways in which we can try to approximate fully continuous automata -- and investigate to what extent similar properties or behaviours arise, and whether new properties can arise unique to continuous spaces.

What if our states were truly continuous -- any value (or at least, any value between 0.0 and 1.0)?

The reaction-diffusion model was proposed by Alan Turing to describe embryo development and pattern-generation (Turing, A. The Chemical Basic for Morphogenesis.); it is still used today in computer graphics (Greg Turk's famous paper). RD systems and other differential equation systems can be approximated using continuous automata.

One approach to simulating RD using CA is the Gray-Scott model, as described in Pearson, J. E. Complex Patterns in a Simple System. A browser-based example is here.

There is a wonderful archive of this model at this webpage, including many great video examples of the u-skate world, and even u-skate in 3D.

Some of these systems share resemblance with analog video feedback (example, example), which has been exploited by earlier media artists (notably the Steiner and Woody Vasulka).

Is it possible to completely eliminate discreteness in all aspects, to create a truly continuous CA? To do so, let's return to our original definition of a CA, and for each component in turn, change discrete into continuous:

States: In this case, the states are not discrete (such as 0 or 1) but belong to a continuum (such as the linear range 0.0 to 1.0). The Hodgepodge model pointed down this path. With a continuous range of states, the transition rule can no longer be a simple lookup table, but instead must map continuous ranges. Comparators can be used to segment continuous space into ranges, and drive control flow, but the use of control flow implies that the output of the transition rule is still principally discontinuous.

Transition functions: One step further requires that the transition rule be expressible as a purely mathematical function, that is predominantly smooth. That is, all transition rules are combined into a single function, which handles both continuous input and produces continuous output. A sigmoid function, for example, is a continuous input & output function that nevertheless approximates the states of discrete functions.

Another option here is to use probabilistic functions. Finding a continuous system whose behaviours persist with the addition of some random noise is tantamount to finding an interesting system that is robust to perturbations -- a useful feature for anything that must interact with the real world!

Neighborhood: Instead of simply considering whole neighbor cells, we may want to apply some kind of weighted average over the surrounding region -- a sampling "kernel". Proper weighting of a kernel can eliminate much of the artifacts due to regular grid spacing. This is similar to how we can apply certain kinds of blur to images, such as Gaussian blur.

The kernel could be simply expressed as an inner and outer radius, for example, or an ideal distance with sampling weighted according to a function of distance from this radius. This is like the subtraction of a smaller blur from a larger blur.

If radii are not expected to change, then kernel locations and weights can be pre-computed. Nevertheless, continuous neighborhood sampling can easily become processor-intensive. It may also be viable to explore a statistical sampling strategy, selecting each time only a random sub-set of the possible sampling locations to create a cheaper approximation of continuous sampling.

Another option is to apply an intermediate process of diffusion -- i.e. blur -- across the entire space between each application of the transition rule. However it is important that the diffusion kernel is mass-preserving -- that is, that repeated applications of the blur will not make the sum of all cell values greater or lesser.

Time: How can we turn discrete steps in time into a smooth flow? Instead of simply outputting a new state, change may be spread over time as a differential. That is, what is output from the transition function is an offset to accumulate to the current state.

This offset may also be distributed over a weighted neighbourhood, rather than a single state.

Another possible strategy to explore is delayed application (i.e., spreading the double-buffering over continuous time): maintaining copies of past and future cell states and interpolating between them. This can be used to smoothen the visual output of the CA, and also to support sampling the field at arbitrary points of time between frames.

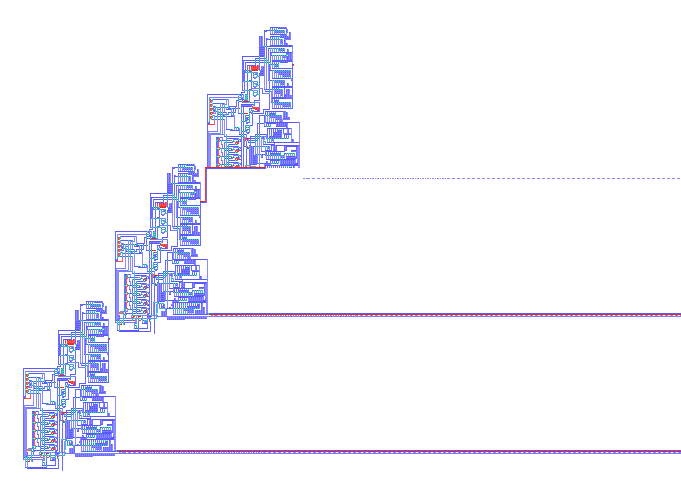

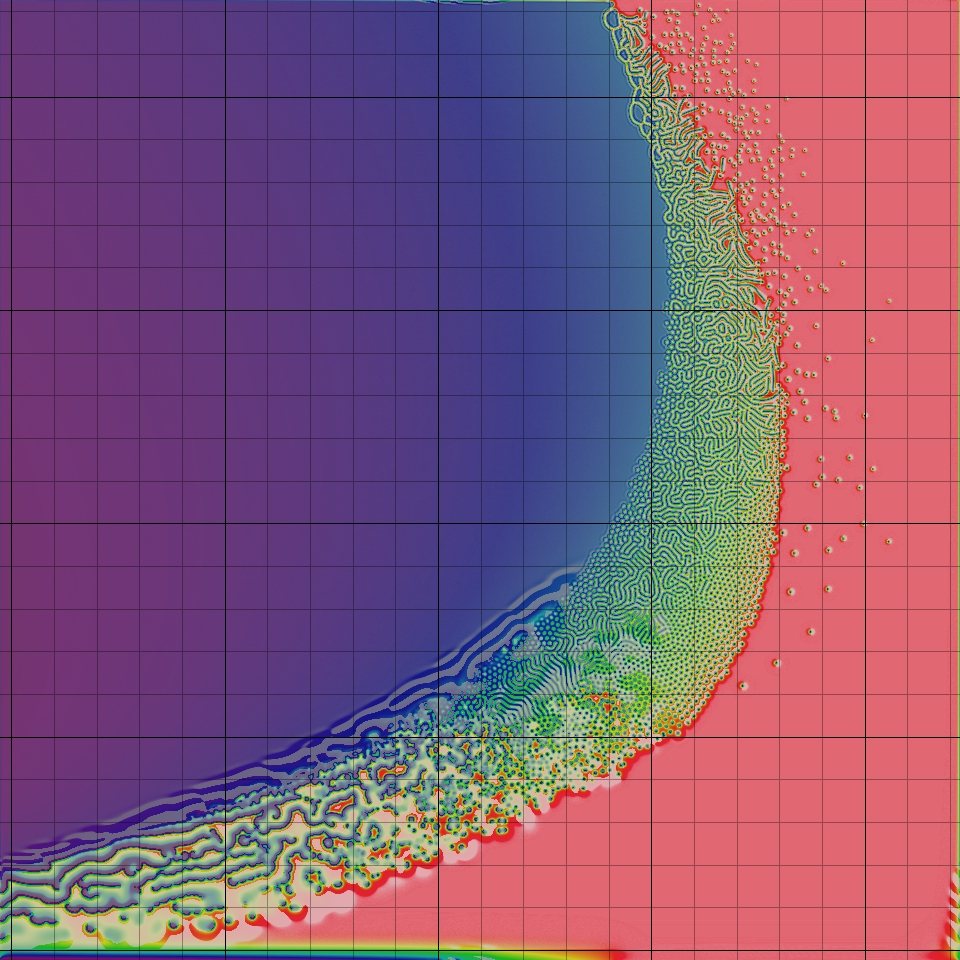

SmoothLife uses a discrete grid, but all of states, kernel, and transition functions are adjusted for smooth, continuous values. A disc around a cell's center is integrated and normalized (i.e. averaged) for the cell's state, and a ring surrounding this is integrated & normalized (averaged) for the neighbor state. Cell transition functions are expressed in terms of continuous sigmoid thresholds over the [0, 1] range, and re-expressed in terms of differential functions (velocities of change) to approximate continuous time. Paper here. By doing so, it removes the discrete bias and leads to fascinating results. Another implementaton. Taken to 3D. In effect, by making all components continuous, it is essentially a simulation of differential equations. Here is a great explanation of the SmoothLife implementation, with a jsfiddle demo

Lenia continues in the spirit of SmoothLife, and has been extensively explored & documented to identify over 400 different organisms, occuping distict environmental niches (different physical constants), with various locomotive patterns catalogued, etc.