Some of the most beautiful, fascinating or strange phenomena of nature can be understood as emerging from the behaviors of interacting agents. Widely acknowledged examples include the murmuration of birds (or swarming insects, schools of fish), and the societal 'superorganisms' of ant colonies. We have come to understand that despite the obvious organization that we see at the macro-scale, there is no hierarchical center of coordination, but rather the whole emerges from simple interactions at local levels. These have been suggested as examples of emergence, or of self-organization. Which is to say, the whole is greater than a naive sum of its parts.

Agent-based models, or multi-agent systems, attempt to understand how non-trivial organized macro-behavior emerges from individuals, known as agents, who are typically mobile, and sense and respond to their world primarily at a local-level. Agent-based abstractions have arisen somewhat independently in several fields, thus their definition can vary widely. However, in most cases, agent-based models consist of populations that typically operate in parallel within a spatial environment. Each autonomous agent interacts locally within an environment populated by other agents, but behaves independently without taking direct commands from other agents nor a global planner or leader.

Agent-based models have applications from microbiology to sociology, as well as video games and computer graphics. As a biological approximation, an agent could refer to anything from an individual protein, virus, cell, bacterium, organism, or deme (a population group). Agent systems also share many features with particle systems, and the two are sometimes conflated.

Just like CA, agents sense and act at local distances, and at times, the self-organizing behavior of systems of even relatively simple agents can be unpredictable, complex, and generate new emergent structures of order. But unlike CA, which roots a program in a particular spatial location (the cell), an agent-based program is mobile in free space.

The first distinction between CA and agent-based systems are that agents are not typically distributed in a grid, and are quite often mobile: a potentially variable position in potentially continuous space. The second distinction is that agents may have a number of other properties (persistent individual variances) besides position. At the least, a mobile agent may have a direction and/or a velocity.

For our purposes, the Javascript Object is a general container for properties, and may serve as the representation of agents:

let agent = {

pos: [0.5, 0.5], // position, x and y components

vel: [0.01, 0], // velocity, x and y components

size: 0.1,

};

function draw(ctx) {

// draw a circle at the agent's position,

// matching the agent's size:

draw2D.circle(agent.pos, agent.size);

}

function update(dt) {

// apply motion:

agent.pos[0] += agent.vel[0];

agent.pos[1] += agent.vel[1];

}

We could also use a vector object to represent position & velocity, which would offer more useful methods (see the Labs page for details on vec2):

let agent = {

pos: new vec2(0.5, 0.5), // position, x and y components

vel: new vec2(0.01, 0), // velocity, x and y components

size: 0.1,

};

function update(dt) {

// apply motion:

agent.pos.add(agent.vel);

}

This agent wanders off the page. As with CA, we can decide how to handle the boundary conditions of an agent-based system in a few different ways, including:

agent.pos.clip(1)agent.pos.wrap(1) if (agent.pos.oob(1))..., by: agent.pos.set(0.5)), or at a random position (agent.pos.set(random(),random())), or some variant, such as random distance from centre of the world (agent.pos.random(random()*0.1).add(0.5)), and possibly also changing other propertiesNote that we might also consider different boundary regions -- it doesn't have to be a square!

The agent also moves very robotically at present. We can give it some "life" by introducing variations into its motion, suggestive of it making decisions in response to an environment.

The simplest way is to introduce stochastic changes to the velocity in direction and magnitute (speed). For direction, we would typically want to turn up to a certain limit (in radians), with equal chance of clockwise and anticlockwise rotation: agent.vel.rotate((random()-0.5)*turnfactor). For speed, we can randomize the length of the velocity up to a certain limit: agent.vel.len(random()*maxspeed)

The result is a random walk. Random walks are a well-established model in mathematics, with a physical interpretation as Brownian motion -- though, a more physically accurate form of Brownian motion would update the velocity sporadically (modeling random collision by a particle), rather than on every frame.

Essentially, for an agent a random walk involves small random deviations to steering. This form of movement is widely utilized by nature, whether purposefully or simply through environmental interactions. Can you think why?

A good way of seeing why random walks work is to deploy a population of agents, rather than a single one. We can do this by storing our agents in an array:

let agents = [];

let population_size = 24;

function reset() {

for (let i=0; i<population_size; i++) {

// create a randomized agent:

let agent = {

pos: new vec2(random(), random()),

vel: vec2.random(),

size: 0.1,

};

// store in population array:

agents[i] = agent;

}

}

function update(dt) {

// iterate over population:

for (let agent of agents) {

// update agent as before

}

}

function draw(ctx) {

// iterate over population:

for (let agent of agents) {

// draw agent as before

}

}

At this point, we have enough to constitute an agent-based model or multi-agent system, and we can turn our attention to the components of agents and systems. Here are some of the features often considered in agent-based models:

Our agent however still lives in a void, with no environment to respond to. Even the simplest organisms have the ability to sense their environment, and direct their motions accordingly; they depend on it for survival.

One of the simplest examples is chemotaxis. Chemotaxis is the phenomenon whereby somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell or multicellular organisms direct their movements according to certain chemicals in their environment. This is important for bacteria to find food (for example, glucose) by swimming towards the highest concentration of food molecules, or to flee from poisons (for example, phenol). For example, the E. Coli bacterium's goal is to find the highest sugar concentration (see video below). In multicellular organisms, chemotaxis is critical to early development (e.g. movement of sperm towards the egg during fertilization) and subsequent phases of development (e.g. migration of neurons or lymphocytes) as well as in normal function. wikipedia

Sensing a concentration is rather like smell: the feature being detected is local to the agent, but is not a solid object with a distinct boundary. It is diffuse: it seems instead to occupy all parts of space to varying degrees. We model such kinds of spatial properties as intensity fields, such as density fields, probability fields, magnetic fields, etc. Fields occupy all space but in different intensities. But since our simulations are limited in memory, we simulate such continuous fields with discrete approximations, such as grids. Thus we can re-use the field2D to represent enviornmental features for agents to sense.

The choice of environment agents will respond is just as important as the design of agents themselves, including both its initial state and its continuous processes. If the field is entirely homogenous, in which there are no spatial variations, there is nothing significant to sense. On the other hand, if the field is too noisy, it can be too difficult to make sense of. How can we make a better environment?

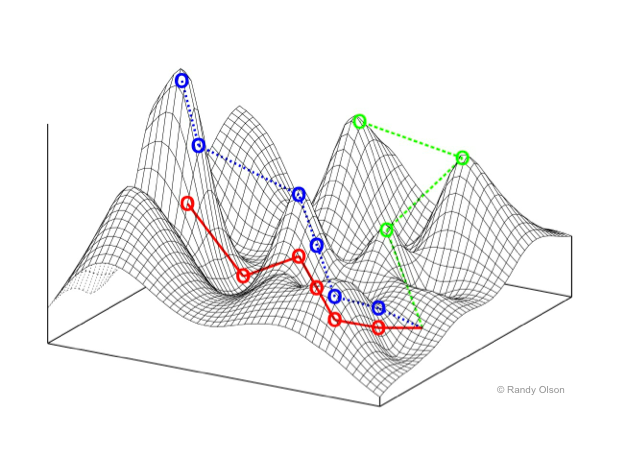

It is helpful to think of the environment as a landscape, with mountain tops where the intensity is high, and valleys where the intensity is low. (Keep this image in mind -- we'll return to this again.)

What makes an interesting landscape to explore & make sense of? A homongenous landscape is like a flat plain -- no place is better than any other. But a noisy landscape is like a city block designed by a madman -- difficult to do anything but get lost. Perhaps one that has an interesting distribution of hills and valleys; where height (intensity) tends to be more similar at shorter distances but tends to be more different at larger distances.

Law of requisite variety: The term 'variety' was introduced by W. Ross Ashby to denote the count of the total number of states of a system. The condition for dynamic stability under perturbation (or input) was described by his Law of Requisite Variety. If a system is to be stable, the number of states of its control mechanism must be greater than or equal to the number of states in the system being controlled. (Paraphrased: if an agent is to exploit the ways of living of an environment, it must have at least the variety of complexity of the environment; or, if a landscape is to satisfy the complexity of its agents, it must have at least the variety of complexity of them.)

Here's a single central "intensity mountain", by computing the distance from the centre:

let dim = 256;

let sugar = new field2D(dim);

let center = new vec2(0.5, 0.5);

sugar.set(function(x, y) {

// convert x, y in to 0..1 range:

let p = new vec2(x / dim, y / dim);

// get distance from center:

let d = p.distance(center);

// make concentration high at center, lower with increasing distance:

return 1 - d;

})

Or, for a more interesting and variegated landscape, we can start from uniform noise, and then smoothen it out:

// fill with uniform noise

sugar.set(function(x, y) { return random(); });

// smoothen it out by long-range diffusion:

sugar.diffuse(sugar.clone(), sugar.width, 100);

// make it vary between 0 and 1:

sugar.normalize();

Or, we could design a CA to generate an interesting landscape, such as using a stochastic Monte Carlo process that prefers making neigbhour cells more similar, starting from a field of noise.

// fill with uniform noise

sugar.set(function(x, y) { return random(); });

// run a stochastic CA for a while:

for (let i=0; i<dim*dim*40; i++) {

// pick a random cell:

let x0 = random(dim);

let y0 = random(dim);

let v0 = sugar.get(x0, y0);

// pick a random neighbor:

let x1 = x0 + random(3)-1;

let y1 = y0 + random(3)-1;

let v1 = sugar.get(x1, y1);

// average them:

let v2 = (v0 + v1)*0.5;

// and update cell with this new value

sugar.set(v2, x0, y0);

}

// make it vary between 0 and 1:

sugar.normalize();

The simplest way to sense a field by "smell" is to sample the field's value at the agent's location. (More accurately, we could sample at the location of a sense-organ on the agent's body).

We could compute the nearest cell index to the agent/sensor location, and then get the value:

// scale position (0..1) to field cell width

// and use Math.floor to round this to a whole number:

let x = Math.floor(agent.pos[0] * sugar.width);

let y = Math.floor(agent.pos[1] * sugar.height);

// get field value at this cell:

agent.sense = sugar.get(x, y);

This is fine so long as we think of the environment as being really made up of discrete blocks in a grid. But in many cases, our grid-based field is only a discrete approximation of a continuous field. In that case, sensing single discrete cells breaks the approximation. What we really want is an approximate value taken between all the nearest cells. We can do this by bilinear interpolation between the four nearest cells. That just means a weighted average: weighted according to which ones are closer or further from the specific agent position. This involves a lengthier bit of code, so the field2D object provides a convenient method for us:

// get an interpolated value from the field,

// using the nearest four cells to the agent's position:

agent.sense = sugar.sample(agent.pos);

We can test whether this is working by for example setting the hue of an agent before drawing:

// before drawing the agent:

draw2D.color = hsl(agent.sense);

Once we have a sense, how should we respond? Here we need to equip our agent with some capabilities of taking action, and likely decision-making, sometimes known as action selection, that uses the input of sense to map to the output of action, in order to achieve a desired result. (The random walker's action was to change velocity, while decision-making was a simple random choice.)

When we look at microbiology we can find some remarkably simple action & decision-making mechanisms to achieve effective goal satisfaction. Let's look at chemotaxis with the E. Coli again:

An E. Coli bacterium lives in a very limited world:

This is a very limited umwelt.

We can certainly model these two modes of locomotion in an agent, by varing the factors of our random walker:

// tumbling behaviour:

turnfactor = 2;

maxspeed = 0.01;

agent.vel

.rotate((random() - 0.5) * turnfactor)

.len(random() * maxspeed * dt);

// swimming behaviour:

turnfactor = 0.01;

maxspeed = 0.5;

agent.vel

.rotate((random() - 0.5) * turnfactor)

.len(random() * maxspeed * dt);

But how does this solve the problem of climbing the sugar gradient?

E. Coli uses a very simple chemical memory to detect whether the concentration at the current moment is better, worse, or not much different to how it was a few moments ago. That is, it detects the differential-as-experienced, or gradient traversed, by measuring its change over time.

Even the actual intensity of the sugar concentration no longer matters; all that matters is whether life is getting better or worse, and acting accordingly. If things are getting better, keep swimming; otherwise, prefer tumbling. With just a few tuning parameters, the method can lead to a very rapid success.

So all we need is to compare the sugar concentration with the agent's memory (a stored member variable) of the concentration on the last time step, and choose the behaviour accordingly (and of course, store our sensed value in memory for the next update).

// sense field here

agent.sense = sugar.sample(agent.pos);

// is life getting worse?

if (agent.sense < agent.memory) {

// tumbling behaviour:

turnfactor = 2;

maxspeed = 0.01;

} else {

// swimming behaviour:

turnfactor = 0.01;

maxspeed = 0.5;

}

// adjusted random walk:

agent.vel

.rotate((random() - 0.5) * turnfactor)

.len(random() * maxspeed * dt);

// remember this:

agent.memory = agent.sense;

Note that not all kinds of landscapes are significant to this life strategy. The strategy only works when the variations of sugar concentration in the environment are fairly smooth, which is generally true for an environment in which concentrations diffuse. Try again with noisy or homogenous environments, and see how well the agent fares.

So far, our sugar field is static. It would be nice to see what a continuously dynamic field offers.

For example, we could let the mouse add more sugar to the space, and watch it gradually diffuse away. Adding sugar in response to the mouse is fairly easy, by making use of the deposit method of field2D. This method accumulates into the field at a point coordinate, adding to its existing values. Note that the coordinate is in the normalized 0..1 range, and that it will spread the value over the nearest four cells:

function mouse(e, pt) {

// add one unit of sugar at the location of the mouse:

sugar.deposit(1, pt);

}

We could also remove the need of human input by creating another kind of agent, as the "source", randomly wandering the space and depositing sugar as it goes.

This might not be completely effective to attract agents, as there can be large spatial discontinuities. If agents happen to be on part of a drawn path, they might follow it, but otherwise they are unlikely to find it.

To create a smoother gradient, we must diffuse the field continuously. To add continuous dynamics, we need to add field processing to our update() routine. And since the diffuse() method requires a distinct source field, we'll need to double buffer like before:

let sugar_past = sugar.clone();

function update() {

// swap fields:

let tmp = sugar_past;

sugar_past = sugar;

sugar = tmp;

// diffuse it

sugar.diffuse(sugar_past, 1);

//... update agents as before

}

Now the agents are able to find the areas of sugar more easily -- and might even show something like trail-following.

We might also notice that even when the sugar is quite dissipated, the agents can still find the strongest concentrations. If we don't find this realistic, one thing we might consider adding is a low level of background noise. The rationale is that even if sensing is perfectly accurate, small fluctuations in the world (such as due to the Brownian motion of water and sugar molecules) make it impossible to discern very small differences. The randomness added must be signed noise, balanced around zero such that overall the total intensity is statistically preserved. Note that the amplitude of this noise will have to be extremely high if it is applied before the diffusion, or very low if applied after diffusion. The effective results are also quite different.

// applied after sugar.diffuse:

// use field2D.map() to modify a cell value

// adding a small random deviation

// whose average is zero

sugar.map(function(v) {

return v + 0.1*(random() - 0.5);

});

Or instead, we could add small deviations to the sensors in the agents themselves, emulating a limited accuracy of sense:

agent.sense = sugar.sample(agent.pos) + 0.1*(random()-0.5);

If we are continuously adding sugar, it will accumulate over time, and the more we draw, the more the screen tends to fill with grey. This is because our diffuse() method spreads intensity out, but does not change the total quantity. We need some other process to reduce this total quantity to make a balance. One way to do that is to add a very weak overall decay to the field -- as if some particles of sugar occasionally evaporate:

// in update():

// multiply all cells with a number slightly less than 1

sugar.mul(0.995);

Of course, our agents aren't just looking for sugar to show it to us -- they want to eat it! We can also add the effect of this on the environment by removing intensity from the field by each agent. We can do this by calling the field2D.deposit() method with a negative argument (i.e. a debit!):

// get the sugar level at this location:

let sense = Math.max(sugar.sample(a.pos), 0);

// update the field to show that we removed sugar here:

sugar.deposit(-sense, agent.pos);

Note however this might lead to some locations getting negative concentrations -- a physical impossibility? We could fix this by clamping the field values as another step:

sugar.map(function(v) {

return Math.max(v, 0);

});

A very different alternative to diffusion, scaling, adding noise, clamping etc. is to use something closer to an asynchronous CA, in continuous process, rather as we did before for field initialization. This makes a more challenging, but more interesting, dynamic landscape for the agents to navigate:

// some swaps:

for (let i=0; i<10000; i++) {

// pick a point at random

let x = random(sugar.width);

let y = random(sugar.height);

// pick a neighbour

let x1 = x + random(3)-1;

let y1 = y + random(3)-1;

// get the values

let a = sugar.get(x, y);

let b = sugar.get(x1, y1);

// pick a random interpolation factor

let t = 0.5*random();

// blend a and b into each other accordingly

let a1 = a + t*(b-a);

let b1 = b + t*(a-b);

// write these values back to the field

sugar.set(a1, x, y);

sugar.set(b1, x1, y1);

}

// some removals:

for (let i=0; i<100; i++) {

let x = random(sugar.width);

let y = random(sugar.height);

sugar.set(0, x, y);

}

Obviously there's a hint here of how it might be interesting to pair our agents with some other CAs for field processes... perhaps the Forest Fire model, for example.

A variety of other taxes worth exploring can be found on the wikipedia page. Note how chemotaxis (and other taxes) can be divided into positive (attractive) and negative (repulsive) characters, just like forces (as we shall see in steering forces). This is closely related to the concepts of positive and negative feedback and the explorations of cybernetics.

Many arachnids and other organisms perform environmental sensing using a pair of antennae extended from their body; effectively 'sampling' the environment at two physical locations. What advantage might this have for chemotaxis? Perhaps, by sampling at two points in space, rather than at two points in time, we can determine the field gradient immediately without latency, and perhaps this can create a more responsive and continuous selection of swimming/turning choices?

We can try giving agents two sensors, both ahead of the agent (to draw movement forward) and to the left and right of the agent (to discriminate which direction is better to turn).

Let's call these sensors "antennae". A bit of math is needed to compute where each antenna is located in the world. Starting from a basic vector representing the antenna relative to tha agent, we can then scale, rotate, and translate the location, resulting in a location relative to the world (or, if we had agent pose as a matrix, we could have simply used matrix multiplication):

// antenna is 50% forward and 50% to the left of the agent:

let antennaleft = new vec2(0.5, 0.5);

// compute what this is as a world location:

antennaleft

.mul(agent.size) // scale to agent size

.rotate(agent.vel.angle()) // rotate to agent direction

.add(agent.pos); // move to agent location

With this, and of course also antennaright, we can sample the environmental field at both locations to get two sensor values:

let smellleft = sugar.sample(antennaleft);

let smellright = sugar.sample(antennaright);

Now the decision-making can respond to these values. We might consider which direction has a better smell (left or right), we might consider the difference between the smells, we might consider the total of the smells too, in order to determine which way to turn, and how much to turn:

It turns out that this strategy is not only great for diffuse fields, but also can function very well for following narrow lines of sugar. That is, aligning movement along given "trails" -- paths of more intense chemical markers, such as the pheromone trails laid down by ants:

From here it is relatively trivial to let the agents also create the trails, as well as following them:

This process is integral to the agents navigating city data in the Infranet artwork:

Stigmergy is a mechanism of indirect coordination between agents by leaving traces in the environment as a mode of stimulating future action by agents in the same location. For example, ants (and some other social insects) lay down a trace of pheromones when returning to the nest while carrying food. Future ants are attracted to follow these trails, increasing the likelihood of encountering food. This environmental marking constitutes a shared external memory (without needing a map). However if the food source is exhausted, the pheromone trails will gradually fade away, leading to new foraging behavior.

Traces evidently lead to self-reinforcement and self-organization: complex and seeminly intelligent structures without global planning or control. Since the term stigmergy focuses on self-reinforcing, task-oriented signaling, E. O. Wilson suggested a more general term sematectonic communication for environmental communication that is not necessarily task-oriented.

Stigmergy has become a key concept in the field of swarm intelligence, and the method of ant colony optimization in particular. In ACO, the landscape is a parameter space (possibly much larger than two or three dimensions) in which populations of virtual agents leave pheromone trails to high-scoring solutions.

Related environmental communication strategies include social nest construction (e.g. termites) and territory marking.

Being able to leave pheromones behind depends on having a specific signature marker in space, such as a particular smell. A simple way to emulate this is to have a field for each pheromone. For example, we may want one pheromone to signal "food this way", and another to signal "nest this way". (An alternative method would be to use a single field and use a different R, G, B channel for each pheromone in that field; but for simplicity here we'll go with multiple fields.)

To draw multiple fields, we can turn on blending and apply different colors for each one:

function draw() {

draw2D.blend(true);

draw2D.color("navy");

phero1.draw();

draw2D.color("orange");

phero2.draw();

draw2D.blend(false);

... now draw agents

}

We already saw in the chemotaxis example how to leave trails in a field, as well as how to let these diffuse and dissipate in order to attract more distant agents and make way for new trails to be made, and similar processing will be needed for each pheromone field. And we saw how use pairs of antennae can estimate the spatial gradient of the field, and turn accordingly.

Here's a start in that direction:

Stigmergy, and other agent behaviours as seen in this course section, were utilized in the Archipelago series of works by Artificial Nature:

If we want to extend our model to support death, such as being eaten by a predator, infected by a disease, starvation, poison, fire, etc., we will need a way to remove items from our array of agents. Assuming that we can mark death by some property (such as a.dead = true), you might expect to remove it from the agents array as follows:

if (agents[n].dead) {

agents.splice(n, 1);

}

(Note that

delete agents[n]won't work at all, it doesn't reshuffle the array to accommodate the gap, it just leaves the gap right there.)

Similarly, if an agent gives birth, you might expect to add the child as follows:

if (child) {

agents.push(child);

}

But in general, adding to or removing from an array is not safe while iterating the array, which is almost certainly the time that you would want to do it. The reason is that you may end up skipping an item, or trying to iterate over an item that no longer exists, or visiting an item twice, because the exact positions of items and the array length have changed. This is one of the classic problems commonly encountered in many imperative programming languages (e.g. C++ too).

Here are two suggested solutions:

It is safe to splice and push while iterating backwards, because reshuffling an array only affects later items:

let i = agents.length;

while (i--) {

let a = agents[i];

//.. do stuff,

// possibly setting dead = true

// or creating a chil

if (dead) {

// remove safely:

agents.splice(i, 1);

} else if (child) {

// add a child:

agents.push(child);

}

}

Note that in this case, new births will not be visited until the next frame. This is probably what you want, since otherwise you might end up creating an infinite loop!

Rather than modifying the array in-place, we build a new array on each iteration, and replace the original when done. This has the advantage of working with for-of loops:

// create new array for the next frame's population:

let new_population = [];

for (let a of agents) {

//.. do stuff,

// possibly setting dead = true

// or creating a child

// preserve only living agents:

if (!dead) new_population.push(a);

// add a child?

if (child) new_population.push(child);

}

// replace original

agents = new_population;

Note that new children are added to newagents, ensuring they are visited next frame. If we added them to agents, they would also be included in the iterating for loop on the current frame, which could potentially lead to an infinite loop.

Clearly if a population ever drops to zero, we will never see any organisms again. This may be problematic for an ongoing exhibition! Methods to overcome this include preventing death of the last (few?) creatures, or introducing new randomly seeded organisms (perhaps out of view) at low population sizes.

At the other end, a population that grows excessively large can slow down the simulation, perhaps even crash it. Again, this is problematic for an ongoing exhibition. It may be necessary to set an absolute population size limit (preventing new agents from being added at this point).

It would be preferable if a simulation didn't hit these externally-imposed limits; or at least, not very often. It would be preferable if some kind of endogenous forces, some processes that are part of the world itself, automatically avoid these events. Perhaps an overly-large population is sporadically decimated by extreme weather events, or a mass infection, for example. Whatever the solution, it involves macroscopic behaviour (population size) affecting microscopic behaviour (individual agents reproduction/death).

If we are careful to apply an energetic cost to every agent activity, and energetic gain through eating/respiration/metabolism, we can count the total energy balance over the entire system on each frame. We can then apply that energy deficit/surplus back into the system in an environmental way, ensuring that the total energy of the system remains constant.

This is the population's total energy expenditure (which incidentally may also be a useful indicator of the liveliness of a system).

sugar.sum())Adding together the population and environmental totals gives is the measure of the total available energy in the world. The goal is for this total available energy to remain fairly constant, at an ideal energetic carrying capacity. Compute the difference of available - ideal: if there is surplus, remove it from the environment; if there is deficit, distribute new energy to the environment. So, if this total energy level is below the chosen carrying capacity for the world, we can then introduce energy back in, to ensure that the whole system doesn't wind down to zero. Re-introducing energy could be done by distributing it somewhat randomly in the space, or by probabilistic expansion of a current growth area, etc. Similarly, if it somehow exceeds the capacity, it can be randomly or gradually removed from the environment.

Energy dynamics should help keep a population size in reasonable ranges, however it may still be necessary to also implement the hard limit cases.

Here combined with Chemotaxis:

As well as communicating via fields, agents may be aware of each other directly; perhaps through distal senses such as vision or hearing. Since agents are mobile, the set of agents that are close neighbours to another can change over time. We thus need to add routines to compute lists of near-neighbours on each frame.

The simplest, naive method is to compare each agent against each other; being careful to skip the test against oneself:

// for each agent:

for (let a of agents) {

// for each possible neighbour agent:

for (let n of agents) {

// don't compare with self:

if (a == n) continue;

//...

}

}

This method would then filter the results by constraints such as distance (range of hearing/sight) and perhaps angle, colour, etc:

// find neighbours:

// for each agent:

for (let a of agents) {

// we will create lists of agents that are

// visible neighbours, or colliding neighbours

// of agent `a`:

a.neighbours = [];

a.collisions = [];

// consider all possible agents:

for (let n of agents) {

// don't compare with self:

if (a == n) continue;

// get relative vector to neighbour:

let rel = n.pos.clone().sub(a.pos);

// wrap around world boundaries?

//rel.relativewrap();

// turn `rel` into a's directional frame:

rel.rotate(-a.vel.angle());

// get distance

let distance = rel.len();

// take into account agent sizes:

distance = Math.max(distance - (a.size + n.size), 0);

// detect overlap:

if (distance <= 0) {

// they are overlapping

a.collisions.push(n);

} else if (distance < visible_range) {

// they are in sight range

// check visible angle:

if (Math.abs(rel.angle()) < field_of_view) {

// agent `a` can see agent `n`

// add to list of neighbours

a.neighbours.push(n);

}

} else {

continue;

}

}

}

Notice how:

a.neighbours list on each frame -- otherwise it would grow infinitely! if (a == b) continue)relativewrap to deal with toroidal spaceNote that this naive checking of all agents against all agents isn't especially efficient (it has ON^2 complexity), but for small populations it is quite reasonable. See the note in the labs page on hashspace lookup for a potentially more optimal method using a spatial acceleration structure. Another tip: in some cases we can save some CPU by using the dot product to detect angle similarity between an agent's heading and the relative vector.

In the late 1980s Craig Reynolds proposed a model of animal motion to model flocks, herds and schools, which he named boids. Reynolds' paper Steering Behaviors for Autonomous Characters covers boids as an aggregate of other steering behaviours. The paper has been very influential in robotics, game design, special effects and simulation, and remains well worth exploring as a collection of patterns for autonomous agent movements, so we will work through it in more detail.

His paper breaks agent movement in general into three layers:

steering force = desired_velocity - current_velocity.His paper concentrates on several different steering algorithms. Locomotion is extremely simple -- equivalent to a single force vector on a point mass -- but a more complex (and thus constrained) locomotion system could be swapped in without changing the steering model significantly. Action selection is not dealt with, but also arguably independent.

Here for example is the "seek" and "flee" steering methods, which derive desired velocity from a the relative vector toward (or away from) a target point. Given a desired velocity, the steering force is obtained by subtracting the current velocity:

Here for "seek" extended with obstacle avoidance. The basic concept is to project forward a rectangle of the same width as the agent, up to a limit of visible range, and see if it intersects with the obstacle. If it does, a lateral force opposite in magnitude to the expected overlap is added to prevent a collision happening:

Reynolds' most significant contribution combined several steering forces to a proposed model of animal motion emulating flocks, herds and schools. Each agent, or "boid", follows a set of rules based on simple principles:

In addition, if none of the conditions above apply, i.e. the boid cannot perceive any others, it may move by random walk.

To make this more realistic, we can consider that each boid can only perceive other boids within a certain distance and viewing angle. We should also restrict how quickly boids can change direction and speed (to account for momentum). Additionally, the avoidance rule may carry greater weight or take precedence over the other rules. Gary Flake also recommends adding an influence for View: to move laterally away from any boid blocking the view.

Evidently the properties of a boid (apart from location) include direction and speed. It could be assumed that viewing angle and range are shared by all boids, or these could also vary per individual. The sensors of a boid include an ability to detect the density of boids in different directions (to detect the center of the flock), as well as the average speed and direction of boids, within a viewable area. The actions of a boid principally are to alter the direction and speed of flight.

The behavior of an agent depends on the other agents that it can perceive (the neighborhood), as described above. Once a set of visible neighbors is calculated, it can be used to derive the steering influences of the agent.

Note that since the agents are dependent on each other, it also makes sense to perform movements and information processing in separate steps. Otherwise, the order in which the agent list is iterated may cause unwanted side-effects on the behavior. (This multi-pass approach is similar in motivation to the double buffering required in many cellular automata).

Several choices have to be made to balance the forces well -- how far agents can see, over what radius, what kind of clipping on the strength of forces, or clipping on the resulting velocities, what range and sensitivity does the avoidance force have, what relative weight does the center force have, etc. Varying these can produce quite different behaviours. Do some forces (e.g. avoidance) completely override others? Do some forces apply only intermittently (by probability)? Etc.

See one example of flocking boids here:

Here it has been extended with the most simple start of social dynamics (cohesion of hue):

Here's another one:

One of the attractive features of the Boids model is how they behave when attempting to avoid immobile obstacles. For a small number of obstacles, we can simply use a list with a similar avoidance force routine.

Flocking has become integral to many media artworks, including again in the Artificial Nature series, for example: